[Image - 30 St Mary Ax by Urban Orienteer]

I'd like to begin Urban Orienteer by tracing the series of discoveries, thoughts and events that have influenced my current collaboration with Mark at Dancing Eye. The working title for the project is 'In the Shadows of the Crystal Palace'. Here Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace serves as a motif in our exploration the ambivalence in Western democracy's valorisation of transparency as an ideal. Formulated as a question: "What happens when the demand for transparency is realised only asymmetrically, and when a desire for control on behalf of the authorities gains autonomy over and against citizens' demands for accountability?" The simple answer: "read the news!"

Consider concerns over police brutality following G20, the British police's deployment of Forward Intelligence Teams (FIT), their use of spotter cards to help identify and track particular individuals, and their classification of otherwise lawful protestors as domestic extremists. More mundanely there is also the pervasive use of CCTV in British towns and cities. What these developments seem to intimate is an interest, at the local and State level, in maintaining, if not a monopoly of violence, then at least a generalised condition of what economists refer to as information asymmetry. If there has to be a divide between the authorities and the rest, then let it be transparent. Increasingly the glass divide is replaced by the two-way mirror. One response has been the formation of FIT Watch; a group who attempt to redress the balance by publishing their own spotter cards of FIT operatives and literally watching the watchers.

Our own reaction is an attempt to explore these issues at the level of ideology. In doing so we hope to counter apathy, and the belief that there is no alternative, by suggesting through art how this situation came about, and provoking others to explore how can we change it. At present Mark and I are working to produce a series of posters for screen-printing. My personal favourite so far is titled 'Crystal Palaces Cast No Shadows':

Consider concerns over police brutality following G20, the British police's deployment of Forward Intelligence Teams (FIT), their use of spotter cards to help identify and track particular individuals, and their classification of otherwise lawful protestors as domestic extremists. More mundanely there is also the pervasive use of CCTV in British towns and cities. What these developments seem to intimate is an interest, at the local and State level, in maintaining, if not a monopoly of violence, then at least a generalised condition of what economists refer to as information asymmetry. If there has to be a divide between the authorities and the rest, then let it be transparent. Increasingly the glass divide is replaced by the two-way mirror. One response has been the formation of FIT Watch; a group who attempt to redress the balance by publishing their own spotter cards of FIT operatives and literally watching the watchers.

Our own reaction is an attempt to explore these issues at the level of ideology. In doing so we hope to counter apathy, and the belief that there is no alternative, by suggesting through art how this situation came about, and provoking others to explore how can we change it. At present Mark and I are working to produce a series of posters for screen-printing. My personal favourite so far is titled 'Crystal Palaces Cast No Shadows':

[Image - Crystal Palaces Cast No Shadows by Urban Orienteer and Dancing Eye]

The decision to create posters came about after Mark and I visited the Tate Modern's Red Star over Russia exhibit, featuring examples of Soviet propaganda on loan from the David King Collection. Mark and I were keen to explore ideas in a visual way, originally to form part of a special edition of Dancing Eye devoted to the theme of War. At the same time I also discovered Mike Holliday's article on the Ballardian website about J.G. Ballard's obscure 'Court Circular'. What caught my attention was not so much the 'Court Circular' itself as the fact that Ballard's intention had been to 'advertise ideas'. In a further two part essay (Part1, Part2) Rick McGrath asks this crucial question of Ballard: "what exactly is he trying to sell?" Applied to our own case this question raised conceptual difficulties we were unable to resolve at that time. What if, in the process of criticising war, we were inadvertently advertising it, perhaps even glamorising it? Further considerations outlined below led us to postpone that project and refocus our efforts on a concern for personal freedom in relation to processes of commodification and diffuse application of techniques of control.

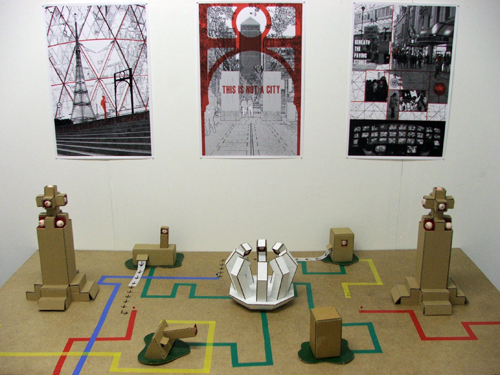

In recent months Mark and I have been experimenting with montages of digital photographs that I've been taking for the project. Back in November we had the opportunity to exhibit three of our test images (pictured below) at the Chocolate Factory studios in Wood Green. The occasion for this was their annual open studio event.

[Image - Installation View of the Urban Orienteer and Dancing Eye collaboration at the Chocolate Factory studios]

I mentioned above that our first concern had been war. Although this theme is not obviously apparent in our current work, it continues to influence the project. A key inspiration was our discovery of Paul Virilio's writings. Of particular interest was his theorisation of the 'logistics of perception': the idea that war has become increasingly mediated by images, and can therefore be fought by means of them. Remnants from this stage of research are Mark's sculptural embodiments of Virilio's Vision Machine (pictured above). Virilio's notion of the 'vision machine' captures the sense of 'sightless vision' that he associates with devices or systems that see on the user's behalf. An example from the contemporary battlefield would be the unmanned drones used by the US Air Force.

Virilio's general concern is the increasing autonomy these systems gain with regard the user, and the way this can actually constrain human perception and encourage the deferral of responsibility. The recent announcement that US drones unencrypted video feeds have been 'hacked by Iraqi insurgents' is unlikely to have shocked Virilio who considers the 'accident' as integral to technological development. Examples of vision machines pertinent for our own project might include smart CCTV systems and gaze-tracking cameras. The former alerts the CCTV operator to 'suspicious' behaviour while the latter actually watches the eyes and viewing pattern of the operator in order to generate a summary of the footage they miss during their shift. I wonder if, aside from the already documented potential for operator abuse, the new unexpected accidents concerning CCTV might arise from lazy gaze trackers and overly suspicious smart cameras. Perhaps these scenarios have already been explored in science fiction.

Around the time we were reading Virilio we also attended an extremely rewarding lecture on Feral Cities and the Scientific Way of Warfare that had been organised by the Complex Terrain Laboratory. The featured speakers were BLDGBLOG's Geoff Manaugh discussing Richard J. Norton's essay Feral Cities, and Antoine Bousquet introducing his book The Scientific Way of Warfare: Order and Chaos on the Battlefields of Modernity. A video of the event can be found here. The unifying theme of the evening was the desire to spatially order an environment in such a way as to minimise contingency and achieve control. As such an implicit connection was made between what military strategists attempt to achieve on the battlefield, and what authorities and city planners might try to achieve in the urban environment by means of what has come to be known as 'Military Urbanism'. I recommend Brian Finoki's blog Subtopia to anyone interested in finding out more.

Given the emerging facts regarding asymmetric and network-centric warfare Mark and I felt that our understanding of war had been anachronistic and remained too heavily influenced by presuppositions of symmetry and reciprocity for us to develop a genuinely critical approach at that time. Our emphasis naturally shifted toward an investigation of 'control' as applied to the urban environment and civil population. Anna Minton's book Ground Control came just at the right time in early 2009. This book deals explicitly with the social and psychological effects of heightened surveillance and the privatisation of public space. The strength of the book lies in its tracing the complex interplay of competing interests, whether of the State, local authorities, or private companies, that help shape the legislation facilitating 'control'. In doing so she offers concrete answers to the question "How did this situation come about?"

Of particular interest is the police initiative known as Secured by Design (SBD). With the encouragement of insurance firms this represents the attempt to literally design out the opportunities for crime. Minton argues not only that this initiative necessarily fails, but also that it actually raises anxiety over crime. Minton traces the development of SBD back to Oscar Newman's principles of defensible space that were intended to curb crime in New York during the 70s. Minton highlights the difference between its original context and that of a post-credit crunch UK where the zeal it has inspired for territorialisation, fortification and surveillance might be misplaced. Combined with policies facilitating the privatisation of public space, in financial and commercial areas such as the City of London, Canary Wharf and Liverpool One, and the use of ASBOs to criminalise otherwise lawful behaviour on the part of specific individuals, the net results are suspicion, exclusion and anxiety. Minton goes on to examine this heightened anxiety over crime that persists despite the evidence that crime is actually falling. Here are brief summaries of her views concerning CCTV and the privatisation of public space.

It is perhaps ironic that the glass facade features so heavily in the new London architecture found in the kinds of private estates Minton criticises. In his book New Glass Architecture Brent Richards noted in passing how, at the beginning of the twentieth century, 'glass became the ideal material to symbolize the incoming new democracy, as monarchy gave way to workers and private domains gave way to public spaces' (p.15). Despite this one of the buildings featured in his book has recently featured in the news not as a symbol of democracy, but rather for its involvement in the overzealous application of anti-terror legislation. This occurred when the journalist Paul Lewis was detained by police under section 44 of Terrorism Act 2000 for taking photographs at 30 St Mary Axe (the Gherkin). A full report and video of the incident can be found here.

Given the emerging facts regarding asymmetric and network-centric warfare Mark and I felt that our understanding of war had been anachronistic and remained too heavily influenced by presuppositions of symmetry and reciprocity for us to develop a genuinely critical approach at that time. Our emphasis naturally shifted toward an investigation of 'control' as applied to the urban environment and civil population. Anna Minton's book Ground Control came just at the right time in early 2009. This book deals explicitly with the social and psychological effects of heightened surveillance and the privatisation of public space. The strength of the book lies in its tracing the complex interplay of competing interests, whether of the State, local authorities, or private companies, that help shape the legislation facilitating 'control'. In doing so she offers concrete answers to the question "How did this situation come about?"

[Image - Broadate Tower Under Construction by Urban Orienteer]

Of particular interest is the police initiative known as Secured by Design (SBD). With the encouragement of insurance firms this represents the attempt to literally design out the opportunities for crime. Minton argues not only that this initiative necessarily fails, but also that it actually raises anxiety over crime. Minton traces the development of SBD back to Oscar Newman's principles of defensible space that were intended to curb crime in New York during the 70s. Minton highlights the difference between its original context and that of a post-credit crunch UK where the zeal it has inspired for territorialisation, fortification and surveillance might be misplaced. Combined with policies facilitating the privatisation of public space, in financial and commercial areas such as the City of London, Canary Wharf and Liverpool One, and the use of ASBOs to criminalise otherwise lawful behaviour on the part of specific individuals, the net results are suspicion, exclusion and anxiety. Minton goes on to examine this heightened anxiety over crime that persists despite the evidence that crime is actually falling. Here are brief summaries of her views concerning CCTV and the privatisation of public space.

It is perhaps ironic that the glass facade features so heavily in the new London architecture found in the kinds of private estates Minton criticises. In his book New Glass Architecture Brent Richards noted in passing how, at the beginning of the twentieth century, 'glass became the ideal material to symbolize the incoming new democracy, as monarchy gave way to workers and private domains gave way to public spaces' (p.15). Despite this one of the buildings featured in his book has recently featured in the news not as a symbol of democracy, but rather for its involvement in the overzealous application of anti-terror legislation. This occurred when the journalist Paul Lewis was detained by police under section 44 of Terrorism Act 2000 for taking photographs at 30 St Mary Axe (the Gherkin). A full report and video of the incident can be found here.

The project finally came together with our discovery of the Crystal Palace as the precursor for Richard's 'new glass architecture'. The palace was originally designed by Joseph Paxton to house The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London's Hyde Park. Intended as a temporary structure, popular demand led to it being reconstructed three years later, in modified form, on Sydenham Hill in south London. The palace remained there until it was destroyed by fire in 1936. The popularity of the building led historian Jan Piggott to refer to it as the Palace of the People in his book of the same name. The palace remained on Sydenham Hill until it was destroyed by fire in 1936. Continuing this sentiment there is an ongoing campaign to build a new Crystal Palace on the Sydenham Hill site by 2014. All that remains of the original site are a number of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins' original dinosaur sculptures in the lower park, and a series of sphinxes that would have guarded the palace entrances on the now empty terrace above. These are overlooked by the Crystal Palace television transmitter.

[Image - Sphinx at Crystal Palace by Urban Orienteer]

Despite the palace's popularity at home its legacy in the history of ideas has been far from unequivocal. For example, in Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is To Be Done? (1863) the figure of the Crystal Palace functioned as the imaginary support for the process of modernisation and the socialist utopia to come. Both Dostoyevsky, in his book Notes From The Underground (1864), and Yevgeny Zamyatin, in the more overtly dystopian We (1921), have offered criticisms of Chernyshevsky’s faith in scientific rationality and transparency. The fact remains that the palace also functioned as the ideological support for British imperialism around the world. Hence the Crystal Palace can stand for the attempt to control or neutralise the outside world, either as commodity or spectacle. Speaking at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 2009 (transcript here) the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk goes further to consider the existence of a fundamental human need to 'immunize existence' through creation of and management of interior spaces, whether architectural or cultural. Hence, referring to Walter Benjamin's treatment of the Parisian arcades in the unfinished Arcades Project, Sloterdijk writes:

In the case of the arcade, modern man opts for glass, wrought iron, and assembly of prefabricated parts in order to build the largest possible interior. For this reason, Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, erected in London in 1851, is the paradigmatic building. It forms the first hyper-interior that offers a perfect expression of the spatial idea of psychedelic capitalism. It is the prototype of all later theme-park interiors and event architectures. The arcade heralds the abolition of the outside world. It abolishes outdoor markets and brings them indoors, into a closed sphere.

Sloterdijk concludes by arguing that if modern men cannot exclude the outside through the creation of insulating interiors they subdue it by internalising it. Contrary to what he describes as a 'current romanticism for openness', he argues that 'people can only be outside to the degree that they are stabilized from within from something that gives them firm support'. We are left in the hands of the architects and planners, hoping from within our apartments that someone will come to pay us a visit. In the meantime Sloterdijk's wager seems to be that our 'foam' of 'relatively stabilized personal worlds' will provide sufficient insulation against the symptomatic expression of 'intolerable ecstasy' that we might associate with the happenings of J.G. Ballard's dystopian novel High-Rise. While we find Sloterdijk's diagnosis compelling, his conclusions seem disappointingly Conservative. In future posts I hope to explore Sloterdijk's discussion of Sphere's further. Unfortunately there is little else available in English translation at this time.

To end I would like to propose another approach to the significance of the Crystal Palace by way of its connection, via Paxton, with the Victoria amazonica water lily. While head gardener at Chatsworth House, Paxton was the first Englishman to succeed in getting the lily to flower in captivity. A popular story has it that Paxton's inspiration for the design of his glass houses came from the structure of the underside of the lily's leaf. What interests us here however is not solely the lily's structure but also its means of reproduction. This can be seen in the video below:

[Video - Giant waterlillies in the Amazon - The Private Life of Plants - David Attenborough - BBC wildlife from BBC Worldwide channel on Youtube]

Here we find that the lily's reproduction is necessarily mediated by the beetle. This it traps for the duration of a day in order to avoid self-fertilisation. The beetle is then released from what Attenborough refers to in the film above as its 'beautiful prison', but only after having picked up another load of pollen with which to fertilise the next lily. Here we propose that an analogy can be supposed between the way the beetle supports the reproduction of the lily, and the way consumers mediate exchange and support capitalism in free-market economies.

"What is to be done?"

The project is intended to culminate this summer with the production of a series of around six screen-prints. This will coincide with the release of the next issue of Mark's publication Dancing Eye. We also intend to host our own exhibition featuring a short film and works by other artists.

No comments:

Post a Comment